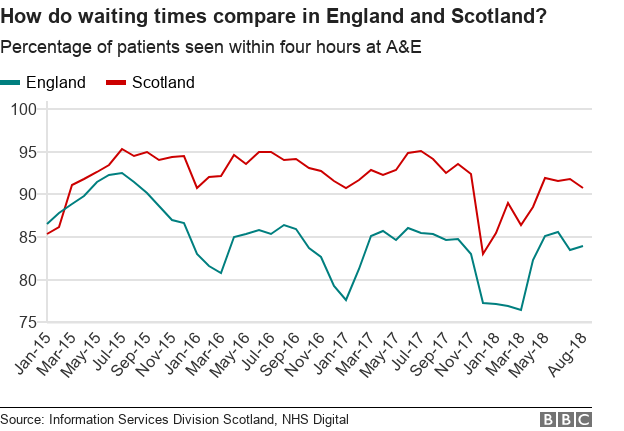

Initially I was interested in visiting the Scottish NHS largely because of their ability to perform better than England at the four hour ED target (see graph below). But after spending some time there - in Dumfries and Galloway, and Glasgow - I realised there's a huge amount more we can learn from Scotland.

As Chris Ham notes, devolution has led to the four national health systems differing considerably in how they are designed but has also reduced the appetite to learn from each other. I want to use this blog to share three key lessons and observations from the Scottish system that are of particular interest. Overall though my main reflection as I returned home was "why don't we talk about the innovations in Scottish healthcare more?".

ED waiting times for England and Scotland. Source: BBC

1. Integration at scale

Integration is the key strategic focus of the NHS in England in coming years - there is no plan b. Yet when we talk about integration, the countries most frequently mentioned are examples like New Zealand, ACOs in the US, or maybe Singapore. Undoubtedly there are examples of outstanding results in these countries. However Scotland serves as a fascinating and highly relatable example close to home.

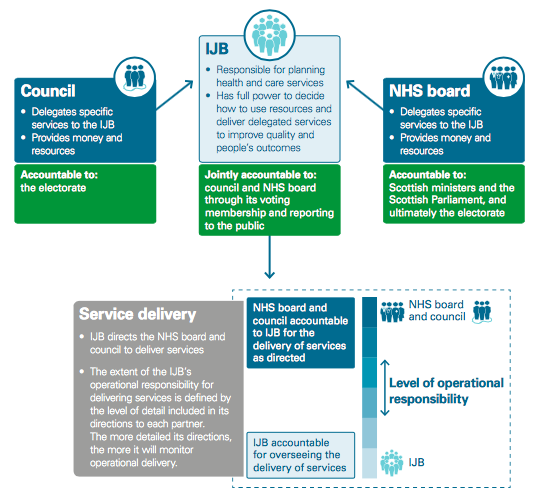

In one of the most significant changes to the NHS since its founding, in 2014 Scotland legislated that Integration Joint Boards (IJBs) should manage health and social funds across Scotland. IJBs now manage more than £9billion in integrated health and care funds across Scotland.

Scotland's IJB Structure (source: Audit Scotland report on integration, 2018)

I visited IJBs in Dumfries and Galloway, and Glasgow.

What struck me about Dumfries and Galloway in particular was its similarities to South Somerset - it has a population of around 160,000. The Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary is similar in size to Yeovil Hospital. I was amazed by the scale of integration I saw there: health and care commissioning and provision was completely aligned under a Chief Officer reporting to the Dumfries and Galloway IJB. In Glasgow City, their IJB had delivered a range of programmes to reduce delays which, alongside a very rigorous and effective hospital approach to managing flow, meant there were only 11 delays for 850 beds in the Glasgow Royal Infirmary (a rate of 1.3%).

The Glasgow Royal Infirmary

Structure clearly isn't everything and, as a recent Audit Scotland report outlined, integrated organisations are a great facilitator but not in themselves sufficient for truly integrated services. Staff in all areas agreed that what matters most is relationships. One member of hospital staff summed it up well:

"Yes we'd probably be collaborating with social care anyway, but we now meet more frequently and can see how money is spent across the system - and how we could improve how it's spent. For example, the other day we saw how much we spend on locum doctors (a lot!) compared to public health campaigns to keep people well. Now we can have the discussions about how we best use our funds for overall health".

Scotland's focus on integration isn't just structural: every area now has to assess progress against nine key priorities (shown below). What's striking about these is how they focus on people, communities and the wider-determinants of health. Although some of the measures are acute (such as reducing non-elective acute bed days), they are balanced with community measures - and all require out-of-hospital action.

Scotland's nine priorities for health and social care (Source: Scottish Parliament)

Scotland's work on integration is of strong relevance to us all as we aim to create seamless, patient-centred care. It shows how structural integration can be done at scale, but also how important relationships and collaboration are to deliver the benefits we all seek.

2. Focus and keeping things simple

The second thing that's noteworthy about the Scottish system is it just seems simpler! It became slightly embarrassing trying to explain the structure of the NHS in England to Scottish colleagues. Just as a small example, Health Improvement Scotland undertakes the functions we have spread out over the CQC, NHSI, NHSE and NICE.

Health Improvement Scotland's organisational aims (see their website for more information)

This simplicity of focus was echoed regarding national responses to specific challenges. What is the government doing about primary care? There's a specific fund identified with clear priorities that when I spoke to front-line GPs appeared both to be understood and having an impact. The same applies to urgent care - there's six actions outlined that will make the biggest difference and a clear 'how to' guide provided across the country on how to roll them out. Staff in hospital talked about them and seemed to understand why they were being focussed on. These strategies appear to be produced through seconding front-line staff temporarily rather than by central organisations.

Colleagues I've spoken to since suggest that Scotland's ability to simplify and focus may be because they're relatively small. However, I'm not sure if bigger has to mean more complex. Maintaining focus and prioritisation in an ever more complex environment is a major challenge but one that Scotland seems to do well.

3. Culture

The third striking thing about health and care in Scotland is the difference in culture. There's a palpable sense that the Scottish NHS is less commercial than the English one. Many services that are outsourced in England are kept in the public sector in Scotland. For example, Glasgow has moved a significant number of residential homes under its own management in part to make it more resilient to care providers becoming insolvent as happened with Southern Cross. This also helps them define and integrate care pathways more easily.

Another cultural factor everyone agreed on was that Scotland's leaders generally stay in post and in the same organisation for much longer. In Dumfries and Galloway, the CEO had been there at least 20 years (initially as the Finance Director). The Deputy Director of Nursing who arranged my visit had been in the same organisation for 28 years. There was a consensus that leaders generally stay much longer and so are aware of the needs of the community and how they need to guide the organisation. This length of service may be due to the rurality of Scotland making it hard to commute between different organisations (and the fact there are fewer of them), but it was generally highlighted as a positive feature.

These cultural differences aren't necessarily good or bad but are a fascinating insight into how a system with a common structure and purpose can create a different cultural feel.

Final thoughts

I've focussed here on some positive reflections on the Scottish system. That's not to say there aren't significant challenges which include worsening life expectancy and serious public health challenges. But they are also innovating at scale in a way that's instructional for us in the English NHS. In Scotland we can see how the NHS has changed since devolution in 1999 with a distinct and more collaborative policy focus.

Go visit!

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-04-14-15-27-52-040-62583d78f636e9115805b2d5.png)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-08-05-09-59-36-465-62ecea08f636e906acfed639.jpg)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-07-28-14-57-17-405-62e2a3cdf636e9180c9835cb.png)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-07-20-10-16-56-533-62d7d618f636ea07987f6668.png)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-07-15-09-55-32-858-62d13994f636ea1398e71aa9.jpg)