I wrote in my previous blog about some of the background to South African healthcare and in this one will share reflections from visiting both private and public hospitals around Johannesburg and Pretoria. As I mentioned previously, the funding level in South Africa – whilst high in total – is largely skewed to private provision leaving funds for public healthcare very stretched.

Private hospitals

Netcare is South Africa's largest private hospital provider and has now expanded to deliver care in the UK too. The Netcare hospitals I saw in Johannesburg were well staffed and equipped, in excellent buildings, and were comparable to good UK hospitals. Staff talked of enjoying working there and being developed by the organisation to progress their careers - for example one nurse I met had started as an HCA and been able to qualify in nursing whilst working there. The clientele in these hospitals are from more affluent communities and insurance premiums are around £100 a month with a cap on the amount and type of care you can receive. One person I discussed insurance with for example stated because they’d had a couple of minor procedures that year, any further care would need to be funded out-of-pocket.

Netcare's values - I particularly like the directness of the last one!

Chris Hani Baragwanath – largest hospital in Southern Hemisphere

Chris Hani Baragwanath in Soweto is the third biggest hospital in the world by beds with almost 3,000 on its huge rambling site. Here their units were well staffed compared to other state hospitals I saw. For example, their ED had five consultants which, whilst small by UK standards, was much better staffed than others I visited. Doctors I spoke to clearly saw working there as a privilege due to the experience they could gain and the prestige of the hospital itself. As one of the largest hospitals in the world, and given the high incidence of trauma in the local area, Bara also has a wealth of international students and fellows particularly from the UK, Germany and the US. Talking to a German medical student studying there, he cited the high exposure to trauma as a key reason for coming:

"You get exposed to more trauma than I'd probably ever see in Germany - gunshots and stabbings all the time - and I get to do much more than I could as a medical student back home. Friday and Saturday nights are completely mad."

German Medical Student at Bara

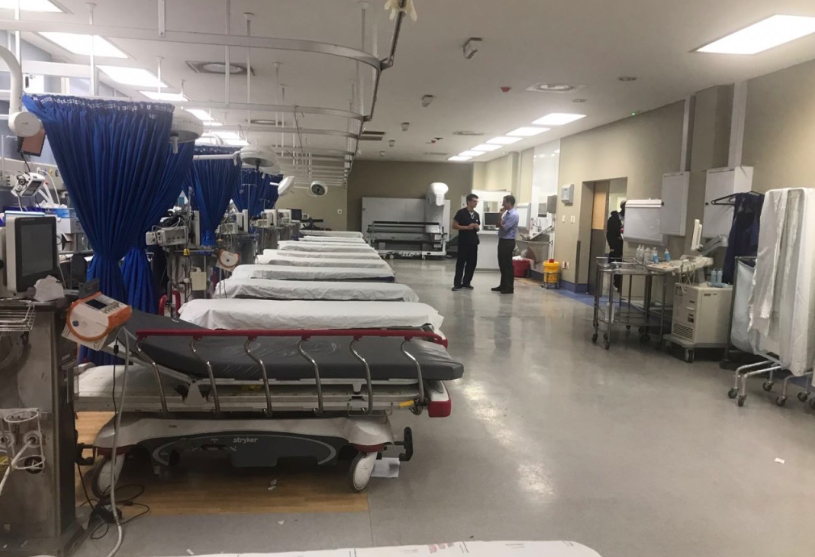

The photo above is of the 15-bedded resus in Bara - the beds were empty ready for the expected surge of stabbings and shootings that peak during the weekends. Despite its huge size, there is no electronic record of the bed state or which patients are where, making managing the site a mind-numbing thought.

Dr George Mukhari Hospital, Pretoria

George Mukhari hospital is a 1,600 bedded tertiary hospital north of Pretoria near the township of Ga-Rankuwa – I’m indebted to Solomon Lebese for arranging this visit. Here I was keen to learn more about management and leadership in hospitals. I met with Sarah Mokgsi, Clinical Executive for the Surgical Cluster, and Professor Lekgwara, Clinical Director and Neurosurgeon. Sarah’s role includes overseeing a department with 80 consultants and significant capacity challenges including a huge arthroplasty backlog.

A contrast to how managers’ time is spent in the UK was the focus on the cost of litigation. Both Sarah and Professor Lekgwara were highly involved in dealing with litigation, and its cost to the hospital was extreme. This was a theme across many of the hospitals I visited: funds are scarce meaning staffing may be lower than needed which leads to litigation which leads to funds being even more scarce.

Meeting leaders from Dr George Mukhari Hospital

Regional Hospitals

In addition to Bara, I visited a Regional Hospital in a township outside Johannesburg. Here the situation was very different to Chris Hani Baragwanath - due to central funding restrictions, vacancies were on hold and as a result staffing was at a critical level and over-crowding rife. The neonatal unit was more than 50% over capacity and experiencing infection outbreaks as a result. There was one medical consultant for over 200 beds. The hospital had a 20 bedded ICU but no ICU consultant. This effectively meant that the hospital was run by Medical Officers who after core medical qualifications generally have on-the-job training rather than any specialty training. These staffing figures were shocking to say the least and the repercussions of such low staffing were clear to see with patients receiving poor care and - in some cases - very poor outcomes. Around half of the consultants I spoke to at the hospital were thinking of leaving due to the stressful environment. This shows the dangerous spiral that can occur when funding restrictions increase work on remaining staff thereby making work conditions untenable for the remainder.

Corruption

The funding challenges faced by many hospitals were perceived by many to be due to corruption in the leaders of government and healthcare. In fact, I didn’t meet anyone who disputed that corruption wasn’t a significant issue. For example, the Ministry of Health in Gauteng province – of which Johannesburg is part – has been investigated for fraud totalling almost £100 million including using public funds for limousines and luxury spa visits. This has been followed by a botched closure of mental health units that saw contracts given to unaccredited NGOs that led to the deaths of 91 patients in 2017. Both these cases have now been publicly accepted by the government but it highlights some of the leadership challenges in progressing the ambitious health goals South Africa has set itself over the coming decade.

Corruption in the headlines

Final thoughts

Visiting South Africa’s hospitals was an invaluable experience I won’t forget. Seeing the contrast between high-end private hospitals and cash-strapped state provision was stark. I was blown away by the amazing and committed clinical leaders I met in state hospitals doing their best for local communities in very challenging times – often sacrificing would could be higher-paid private jobs to do so.

Healthcare in South Africa is undoubtedly more equitable now than it was during apartheid. The government’s National Health Insurance (NHI) initiative is intended to level these inequalities further through introducing a comprehensive insurance model that will see equal access for all – an amazing and highly ambitious goal similar to the principles of the NHS. Whether this succeeds will depend on the quality of leadership driving it forward.

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-04-14-15-27-52-040-62583d78f636e9115805b2d5.png)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-08-05-09-59-36-465-62ecea08f636e906acfed639.jpg)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-07-28-14-57-17-405-62e2a3cdf636e9180c9835cb.png)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-07-20-10-16-56-533-62d7d618f636ea07987f6668.png)

/Passle/5a5c5fb12a1ea2042466f05f/MediaLibrary/Images/6168334917af5b10f4bf1d30/2022-07-15-09-55-32-858-62d13994f636ea1398e71aa9.jpg)